1900 Galveston hurricane

Background Information

This Wikipedia selection is available offline from SOS Children for distribution in the developing world. SOS Child sponsorship is cool!

| Category 4 hurricane ( SSHS) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on September 8, just before landfall. | |

| Formed | August 27, 1900 |

| Dissipated | September 12, 1900 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 150 mph (240 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 936 mbar ( hPa); 27.64 inHg |

| Fatalities | 6000 – 12,000 direct |

| Damage | $20 million (1900 USD) |

| Areas affected | Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, south Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas (particularly around Galveston), much of the Central United States, Great Lakes region, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 1900 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 made landfall on the city of Galveston, Texas on September 8, 1900. It had estimated winds of 135 mph (215 km/h) at landfall, making it a Category 4 storm on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.

The hurricane caused great loss of life. The death toll has been estimated to be between 6,000 and 12,000 individuals; the number most cited in official reports is 8,000, giving the storm the third-highest number of casualties of any Atlantic hurricane, after the Great Hurricane of 1780 and 1998’s Hurricane Mitch. The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 is to date the deadliest natural disaster ever to strike the United States. By contrast, the second-deadliest storm to strike the United States, the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane, caused approximately 2,500 deaths, and the deadliest storm of recent times, Hurricane Katrina, claimed the lives of approximately 1,800 people.

The hurricane occurred before the practice of assigning official code names to tropical storms was instituted, and thus it is commonly referred to under a variety of descriptive names. Typical names for the storm include the Galveston Hurricane of 1900, the Great Galveston Hurricane, and, especially in older documents, the Galveston Flood. It is often referred to by Galveston locals as The Great Storm or The 1900 Storm.

City of Galveston

At the end of the 19th century, the city of Galveston was a booming town with a population of 42,000 residents. Its position on the natural harbour of Galveston Bay along the Gulf of Mexico made it the centre of trade and the biggest city in the state of Texas. With this prosperity came a sense of complacency.

A quarter of a century earlier, the nearby town of Indianola on Matagorda Bay was undergoing its own boom and was second to Galveston among Texas port cities. Then in 1875, a powerful hurricane blew through, nearly destroying the town. Indianola was rebuilt, but a second hurricane in 1886 caused residents to simply give up and move elsewhere.

Many Galveston residents took the destruction of Indianola as an object lesson on the threat posed by hurricanes. Galveston was a low, flat island, little more than a giant sandbar along the Gulf Coast. They called for a seawall to be constructed to protect the city, but their concerns were dismissed by the majority of the population and the city’s government.

Since its formal founding in 1839, the city of Galveston had weathered numerous storms, all of which the city survived with ease. Residents believed any future storms would be no worse than previous events. In order to provide an official meteorological statement on the threat of hurricanes, Galveston Weather Bureau section director Isaac Cline wrote an 1891 article in the Galveston Daily News in which he argued not only that a seawall was not needed to protect the city, but also that it would be impossible for a hurricane of significant strength to strike the island.

The seawall was not built, and development activities on the island actively increased its vulnerability to storms. Sand dunes along the shore were cut down to fill low areas in the city, removing what little barrier there was to the Gulf of Mexico.

Storm history

Origins

The storm’s origins are unclear, due to the limited observation ability at the end of the 19th century. Ship reports were the only reliable tool for observing hurricanes at sea, and because wireless telegraphy was in its infancy, these reports were not available until the ships put in at a harbour.

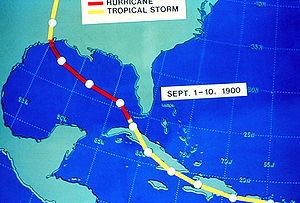

Like most powerful Atlantic hurricanes, the 1900 storm is believed to have begun as a Cape Verde-type hurricane — a tropical wave moving off the western coast of Africa. The first formal sighting of the hurricane’s precursor occurred on August 27, about 1,000 mi (1,600 km) east of the Windward Islands, when a ship recorded an area of “unsettled weather.”

Three days later, Antigua reported a severe thunderstorm passing over, followed by the hot, humid calmness that often occurs after the passage of a tropical cyclone. By September 1, U.S. Weather Bureau observers were reporting on a “storm of moderate intensity (not a hurricane)” southeast of Cuba.

Warning signs

On September 4, the Galveston office of the U.S. Weather Bureau began receiving warnings from the Bureau’s central office in Washington, D.C. that a “tropical storm” had moved northward over Cuba. The Weather Bureau forecasters had no way of knowing where the storm was or where it was going. At the time, they discouraged the use of terms such as tornado or hurricane to avoid panicking residents in the path of any storm event.

Conditions in the Gulf of Mexico were ripe for further strengthening of the storm. The Gulf had seen little cloud cover for several weeks, and the seas were as warm as bathwater, according to one report. For a storm system that feeds off moisture, the Gulf of Mexico was enough to boost the storm from a tropical storm to a hurricane in a matter of days, with further strengthening likely.

The storm was reported to be north of Key West on September 6, and in the early morning hours of Friday, September 7, the Weather Bureau office in New Orléans, Louisiana issued a report of heavy damage along the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts. Details of the storm were not widespread; damage to telegraph lines limited communication. The Weather Bureau’s central office in Washington, D.C. ordered storm warnings raised from Pensacola, Florida to Galveston.

By the afternoon of the 7th, large swells from the southeast were observed on the Gulf, and clouds at all altitudes began moving in from the northeast. Both of these observations are consistent with a hurricane approaching from the east. The Galveston Weather Bureau office raised its double square flags; a hurricane warning was in effect.

The ship Louisiana encountered the hurricane at 1 p.m. that day after departing New Orléans. Captain Halsey estimated wind speeds of 150 mph (240 km/h). These winds correspond to a Category 4 hurricane in the modern-day Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.

Weather Bureau forecasters believed the storm would travel northeast and affect the mid-Atlantic coast. “To them, the storm appeared to have begun a long turn or ‘recurve’ that would take it first into Florida, then drive it northeast toward an eventual exit into the Atlantic.” Cuban forecasters disagreed, saying the hurricane would continue west. One Cuban forecaster predicted the hurricane would continue into central Texas near San Antonio.

Early the next morning, the swells continued despite only partly cloudy skies. Largely because of the unremarkable weather, few residents heeded the warning. Few people evacuated across Galveston’s bridges to the mainland, and the majority of the population was unconcerned by the rain clouds that had begun rolling in by midmorning.

Isaac Cline claimed that he took it upon himself to travel along the beach and other low-lying areas warning people personally of the storm’s approach. This is based on Cline’s own reports and has been called into question in recent years, as no other survivors corroborated his account.

Cline’s role in the disaster is the subject of some controversy. Supporters point to Cline’s issuing a hurricane warning without permission from the Bureau’s central office; detractors (including author Erik Larson) point to Cline’s earlier insistence that a seawall was unnecessary and his belief that an intense hurricane could not strike the island.

The storm

The last train to reach Galveston left Houston on the morning of September 8 at 9:45 a.m. It found the tracks washed out, and passengers were forced to transfer to a relief train on parallel tracks to complete their journey. Even then, debris on the track kept the train’s progress at a crawl.

The 95 travelers on the train from Beaumont were not so lucky. They found themselves at the Bolivar Peninsula waiting for the ferry that would carry them, train and all, to the island. When they arrived, the high seas forced the ferry captain to give up on his attempt to dock. The train attempted to return the way it had come, but rising water blocked its path.

By early afternoon, a steady northeastern wind had picked up. By 5 p.m., the Bureau office was recording sustained hurricane-force winds. That night, the wind direction shifted to the east, and then to the southeast as the hurricane’s eye began to pass over the island.

One of the last messages that reached the mainland was from Cline’s brother at 3:30 p.m., reporting “Gulf rising, water covers streets of about half of city.” Later he regretted not saying the whole city was under water. Shortly thereafter, the telegraph lines were cut.

The highest measured wind speed was 100 mph (160 km/h) just after 6 p.m., but the Weather Bureau’s anemometer was blown off the building shortly after that measurement was recorded. The eye passed over the city around 8 p.m. Maximum winds were estimated at 120 mph (190 km/h) at the time, but later estimates placed the hurricane at the higher Category 4 classification on the Saffir-Simpson Scale. The lowest recorded barometric pressure was 28.48 inHg (964.4 mbar), considered at the time to be so low as to be obviously in error. Modern estimates later placed the storm’s central pressure at 27.49 inHg (930.9 mbar), but this was subsequently adjusted to the storm's official lowest measured central pressure of 27.63 inHg (936 mbar).

Ten refugees from the Beaumont train sought shelter at the Point Bolivar lighthouse with 200 residents of Port Bolivar that were already there. The 85 that stayed with the train died when the storm surge overran the tops of the cars.

By 11 p.m., the wind was southerly and diminishing. On Sunday morning, clear skies and a 20 mph (30 km/h) breeze off the Gulf of Mexico greeted the Galveston survivors.

The storm continued on, and was tracked into Oklahoma. From there, it continued over the Great Lakes while still sustaining winds of almost 40 mph (as recorded over Milwaukee, Wisconsin) and passed north of Halifax, Nova Scotia on September 12. From there it traveled into the North Atlantic where it disappeared from observations.

Impact

Galveston

| “ | First news from Galveston just received by train which could get no closer to the bay shore than six miles (10 km) where Prairie was strewn with debris and dead bodies. About 200 corpses counted from train. Large Steamship stranded two miles (3 km) inland. Nothing could be seen of Galveston. Loss of life and property undoubtedly most appalling. Weather clear and bright here with gentle southeast wind. | ” |

|

—G.L. Vaughan |

||

At the time of the 1900 storm, the highest point in the city of Galveston was only 8.7 ft (2.7 m) above sea level. The hurricane had brought with it a storm surge of over 15 ft (4.6 m), which washed over the entire island. The surge knocked buildings off their foundations, and the surf pounded them to pieces. Over 3,600 homes were destroyed, and a wall of debris faced the ocean. The few buildings which survived, mostly solidly-built mansions and houses along the Strand District, are today maintained as tourist attractions.

As terrible as the damage to the city’s buildings was, the human cost was even greater. Due to the destruction of the bridges to the mainland and the telegraph lines, no word of the city’s destruction was able to reach the mainland. At 11 a.m. on September 9, one of the few ships at the Galveston wharfs to survive the storm, the Pherabe, arrived in Texas City on the western side of Galveston Bay. It carried six messengers from the city. When they reached the telegraph office in Houston at 3 a.m. on September 10, a short message was sent to Texas Governor Joseph D. Sayers and U.S. President William McKinley: “I have been deputized by the mayor and Citizen’s Committee of Galveston to inform you that the city of Galveston is in ruins.” The messengers reported an estimated five hundred dead; this was considered to be an exaggeration at the time.

The citizens of Houston knew a powerful storm had blown through and had made ready to provide assistance. Workers set out by rail and ship for the island almost immediately. Rescuers arrived to find the city completely destroyed. Eight thousand people — 20% of the island’s population — had lost their lives. Most had drowned or been crushed as the waves pounded the debris that had been their homes hours earlier. Many survived the storm itself, but died after several days trapped under the wreckage of the city, with rescuers unable to reach them. The rescuers could hear the screams of the survivors as they walked on the debris trying to rescue those they could. They realized that there was no hope.

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Great Hurricane" | 1780 | 22,000 |

| 2 | Mitch | 1998 | 19,325+ |

| 3 | "Galveston" | 1900 | 8,000 – 12,000 |

| 4 | Fifi | 1974 | 8,000 – 10,000 |

| 5 | "Dominican Republic" | 1930 | 2,000 – 8,000 |

| 6 | Flora | 1963 | 7,186 – 8,000 |

| 7 | "Pointe-à-Pitre" | 1776 | 6,000+ |

| 8 | "Newfoundland" | 1775 | 4,000 – 4,163 |

| 9 | "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 4,075+ |

| 10 | "Monterrey" | 1909 | 4,000 |

| See also: List of deadliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

The bodies were so numerous that burial was not a viable option. Initially, the dead were taken out to sea and dumped; however, the currents of the gulf washed the bodies back onto the beach, so a new solution was needed. Funeral pyres were set up wherever the dead were found. In the aftermath of the storm, pyres burned for weeks. Authorities had to pass out free whiskey to the work crews that were having to throw the bodies of their wives and children on the burn piles.

More people were killed in this single storm than have been killed in the over three hundred hurricanes that have struck the United States since, combined, as of 2006. Thus, the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 remains the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

New York City

The rapidly moving storm was still exhibiting winds of 65mph by the time it reached New York City on September 12, 1900. The New York Times reported that pedestrian walking became difficult and that one death was attributed to the storm. A sign pole, snapped by wind, landed on a 23-year old man, crushing his skull and killing him instantly, while two others were knocked unconscious. Awnings and signs on many building broke and the canvas roofing at the Fire Department headquarters was blown off.

Closer to the waterfront, along the Battery seawall, waves and tides were reported to be some of the highest in recent memory of the fishermen and sailors. Spray and debris were thrown over the wall, making working along the waterfront dangerous. Small craft in New York harbour were thrown off course and tides and currents in the Hudson river made navigation difficult. In Brooklyn, The Times reported that trees were uprooted, signs and similar structures were blown down, and yachts were torn from moorings with some suffering severe damage. Due to the direction of the wind, one of the more infamous spots in New York, Coney Island, escaped the fury of the storm, although a bathing pavilion at "Bath Beach" suffered damage from wind and waves.

Aftermath

Rebuilding

Survivors set up temporary shelters in surplus U.S. Army tents along the shore. They were so numerous that observers began referring to it as the “White City on the Beach.” Others constructed so-called “storm lumber” homes, using salvageable material from the debris to build shelter.

Reporter Winifred Bonfils, a young journalist working for William Randolph Hearst, dressed as a boy and was the first reporter on the line at the flood’s aftermath. She delivered an exclusive set of reports and Hearst sent relief supplies by train.

By September 12, the first post-storm mail was received at Galveston. The next day, basic water service was restored, and Western Union began providing minimal telegraph service. Within three weeks, cotton was again being shipped out of the port.

Prior to the Hurricane of 1900, Galveston was considered to be a beautiful and prestigious city and was known as the " Ellis Island of the West” and the "Wall Street of the Southwest.” . However, after the storm, development shifted north to Houston, which was enjoying the benefits of the oil boom. The dredging of the Houston Ship Channel in 1909 and 1914 ended Galveston’s hopes of returning to its former state as a major commercial centre.

Protection

To prevent future storms from causing destruction like that of the 1900 hurricane, many improvements to the island were made. The first 3 mi (4.8 km) of the 17-foot (5 m) high Galveston Seawall were built beginning in 1902 under the direction of Henry Martyn Robert. An all-weather bridge was constructed to the mainland to replace the ones destroyed in the storm.

The most dramatic effort to protect the city was its raising. Dredged sand was used to raise the city of Galveston by as much as 17 ft (5.2 m) above its previous elevation. Over 2,100 buildings were raised in the process, including the 3,000-ton St. Patrick’s Church. The seawall and raising of the island were jointly named a National Historical Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2001.

In 1915, a storm similar in strength and track to the 1900 hurricane struck Galveston. The 1915 storm brought a 12-ft (4-m) storm surge which tested the new seawall. Although 275 people lost their lives in the 1915 storm, this was a great reduction from the thousands that died in 1900.

The Galveston city government was reorganized into a commission government, a newly devised structure wherein the government is made of a small group of commissioners, each responsible for one aspect of governance. This was prompted by fears that the existing city council would be unable to handle the problem of rebuilding the city.

Today, Galveston is home to a major cruise port, two universities, and a major insurance corporation. Homes and other buildings that survived the hurricane have been preserved, and give much of the city a Victorian look. The seawall, since extended to 10 mi (16 km), is now an attraction itself, as hotels and tourist attractions have been built along its length in seeming defiance of future storms.

The last reported survivor of the Galveston Hurricane of 1900, Mrs. Maude Conic of Wharton, Texas, died November 14, 2004, at the claimed age of 116. (Census records indicate she was younger than that.)

Modern observation and forecasting help ensure that if another storm of similar strength threatens Galveston, the city will not be caught by surprise.