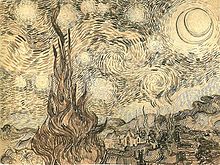

The Starry Night

Background Information

SOS Children offer a complete download of this selection for schools for use on schools intranets. Click here for more information on SOS Children.

|

|

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

|---|---|

| Year | 1889 |

| Type | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 73.7 cm × 92.1 cm (29 in × 36¼ in) |

| Location | Museum of Modern Art ( F612, JH1731) , New York City |

Starry Night (Dutch: De sterrennacht) is a painting by the Dutch post-impressionist artist Vincent van Gogh. The painting depicts the view outside of his sanitarium room window at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (located in southern France) at night, although it was painted from memory during the day. It has been in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, part of the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest, since 1941. The painting is among Van Gogh's most well known works that has inspired thousands of artists, some have even made the painting in their own style.

Genesis

In September 1888, before his December breakdown that resulted in his hospitalisation in Arles, he painted Starry Night Over the Rhone. Van Gogh wrote about this painting:

"... it does me good to do what’s difficult. That doesn’t stop me having a tremendous need for, shall I say the word – for religion – so I go outside at night to paint the stars.'"

In mid-September 1889, following a heavy crisis which lasted from mid-July to the last days of August, he thought to include Starry Night in the next batch of works to be sent to his brother, Theo, in Paris. In order to reduce the shipping costs, he withheld three of the studies, including Starry Night. These three went to Paris with the shipment that followed. When Theo did not immediately report its arrival, Vincent inquired again and finally received Theo's commentary on his recent work.

Subject matter

The centre part shows the village of Saint-Rémy under a swirling sky, in a view from the asylum towards north. The Alpilles far to the right fit to this view, but there is little rapport of the actual scene with the intermediary hills which seem to be derived from a different part of the surroundings, south of the asylum. The cypress tree to the left was added into the composition. Of note is the fact van Gogh had already, during his time in Arles, repositioned Ursa Major from the north to the south in his painting Starry Night Over the Rhone.

In a letter to his brother Theo, van Gogh wrote of it:

"At last I have a landscape with olive trees, and also a new study of a starry sky. ... It’s not a return to the romantic or to religious ideas, no. However, by going the way of Delacroix, more than it seems, by colour and a more determined drawing than trompe-l’oeil precision, one might express a country nature that is purer than the suburbs, the bars of Paris."

Recent commentaries

- Simon Singh, in his book Big Bang, says that Starry Night has striking similarities to a sketch of the Whirlpool Galaxy, drawn by Lord Rosse 44 years before van Gogh's work.

- The painting has been compared to an astronomical photograph of a star named V838 Monocerotis, taken by the Hubble in 2004. The clouds of gas surrounding the star resemble the swirling patterns van Gogh used in this painting.

- Art historian Joachim Pissarro cites Starry Night as an exemplar of the artist's fascination with the nocturnal.

Aims and ends

Van Gogh was not so happy with the painting. In a letter to his brother Theo from Saint-Rémy he wrote:

| “ | The first four canvases are studies without the effect of a whole that the others have . . . The olives with white clouds and background of mountains, also the moonrise and the night effect, these are exaggerations from the point of view of arrangement, their lines are warped as that of old wood. | ” |

Later in this letter, Vincent referred once more to the painting:

| “ | In all this batch I think nothing at all good save the field of wheat, the mountain, the orchard, the olives with the blue hills and the portrait and the entrance to the Quarry, and the rest says nothing to me, because it lacks individual intention and feeling in the lines. Where these lines are close and deliberate it begins to be a picture, even if it is exaggerated. That is a little what Bernard and Gauguin feel, they do not ask the correct shape of a tree at all, but they insist absolutely that one can say if the shape is round or square - and my word, they are right, exasperated as they are by certain people's photographic and empty perfection. Certainly they will not ask the correct tone of the mountains, but they will say: In the Name of God, the mountains were blue, were they? Then chuck on some blue and don't go telling me that it was a blue rather like this or that, it was blue, wasn't it? Good - make them blue and it's enough! Gauguin is sometimes like a genius when he explains this, but as for the genius Gauguin has, he is very timid about showing it, and it is touching the way he likes to say something really useful to the young. How strange he is all the same. | ” |