Actes and Monuments

Did you know...

Arranging a Wikipedia selection for schools in the developing world without internet was an initiative by SOS Children. Sponsor a child to make a real difference.

The Actes and Monuments, popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Christian history and martyrology by John Foxe, first published in English in 1563 by John Day. It includes a polemical account of the sufferings of Protestants under the Catholic Church, with particular emphasis on England and Scotland. The book was highly influential in those countries, and helped shape lasting popular notions of Catholicism there. The book went through four editions in Foxe's lifetime and a number of later editions and abridgements, including some that specifically reduced the text to a Book of Martyrs.

Introduction

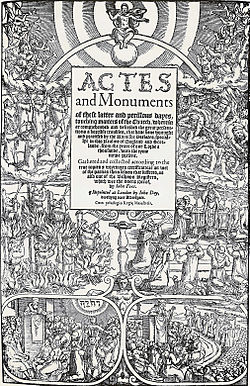

The book was produced and illustrated with over sixty distinctive woodcut impressions and was the largest publishing project ever undertaken in England. Their product was a single volume book, a bit over a foot long, two palms-span wide, too deep to lift with only one hand, and weighed about the same as a small infant. Foxe's own title for the first edition (as scripted and spelled), is Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church. Long titles being conventionally expected, so this title continues and claims that the book describes "persecutions and horrible troubles" that had been "wrought and practiced by the Roman Prelates, speciallye in this realm of England and Scotland". Foxe's temporal range was "from the yeare of our Lorde a thousand unto the tyme nowe present"

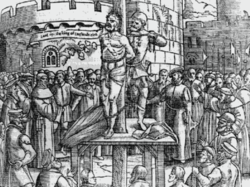

Following closely on the heels of the first edition (Foxe complained that the text was produced at "a breakneck speed"), the 1570 edition was in two volumes and had expanded considerably. The page count went from approximately 1,800 pages in 1563 to over 2,300 folio pages. The number of woodcuts increased from 60 to 150. As Foxe wrote about his own living (or executed) contemporaries, the illustrations could not be borrowed from existing texts, as was commonly practiced. The illustrations were newly cut to depict particular details, linking England's suffering back to "the primitive tyme" until, in volume I, "the reigne of King Henry VIII"; in volume two, from Henry's time to "Queen Elizabeth our gracious Lady now reygnyng".

Foxe's title for the second edition (vol I) is quite different from the first edition where he claimed his material as "these latter days of peril...touching on matters of the Church'. In 1570, Foxe's book is an "Ecclesiastical History" containing "the acts and monuments [no capitals] of thynges passed in every kynges tyme in this realm [England], specially in the Church of England". It describes "persecutions, horrrible troubles, the suffering of martyrs [new], and other such thinges incident ... in England and Scotland, and [new] all other forreine nations". The second volume of the 1570 edition has its own title page and, again, an altered subject. Volume II is an "Ecclesiastical History conteyning the Acts and Monuments of Martyrs" [capitalized in original] and offers "a general discourse of these latter persecutions, horrible troubles and tumults styred up by Romish ['Roman' in 1563] Prelates in the Church". Again leaving the reference, to which church, uncertain, the title concludes "in this realm of England and Scotland as partly also to all other forrine nations apparteynyng".

Title

Actes and Monuments for almost all its existence has popularly been called the Book of Martyrs. The linking of titles is an expected norm for introducing John Foxe's sixteenth century work. William Haller (1963) observed that "[Bishop] Edmund Grindal called it a book of martyrs, and the name stuck." It may have been Grindal's "book of martyrs" (as he had conceived the project), but it was not John Foxe's. Dismayed by the popular misconception, Foxe tried to correct the error in the second edition. That his appeal was ineffective in his own time is not surprising, very few people would even have read it. Continuing this practice in academic analyses is being questioned, particularly in light of Foxe's explicit denial.

"I wrote no such booke bearying the title Booke of Martyrs. I wrote a booke called the Acts and Monumentes ... wherin many other matters be contayned beside the martyrs of Christ.” – John Foxe, The Actes and Monuments (1570)

There is also evidence that the 'martyr' title referred only to the abridgments, as used by John Milner (1795), no friend to Foxe, whose major work Milner situates at the centre of efforts to "inflame hatred" against Catholics in the eighteenth century.

"We find the lying Acts and Monuments of John Foxe, with large wooden prints of men and women, encompassed with faggots and flames in every leaf of them, chained to the desks of many county churches, whilst abridgements of this inflammatory work are annually issued from the London press under the title of The Book of Martyrs."

Work of the English Reformation

Published early in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and only five years after the death of the Roman Catholic Queen Mary I, Foxe's Acts and Monuments was an affirmation of the English Reformation in a period of religious conflict between Catholics and the Church of England. Foxe's account of church history asserted a historical justification that was intended to establish the Church of England as a continuation of the true Christian church rather than as a modern innovation, and it contributed significantly to encourage nationally endorsed repudiation of the Catholic Church.

The sequence of the work, initially in five books, covered first early Christian martyrs, a brief history of the medieval church, including the Inquisitions, and a history of the Wycliffite or Lollard movement. It then dealt with the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, during which the dispute with Rome had led to the separation of the English Church from papal authority and the issuance of the Book of Common Prayer. The final book treated the reign of Queen Mary and the Marian Persecutions.

Editions

John Foxe died in 1587. His text, however, continued to grow. Foxe himself set the precedent, substantially expanding Actes and Monuments between 1563 and 1570. The 1576 edition was cheaply done, with few changes, but for the 1583 printing Foxe added a "Discourse of the Bloody Massacre In France [St. Bartholomew's. Day, 1572]" and other short pieces. The 1596 fifth edition was essentially a reprint of the 1583 edition. The next editor, however, followed Foxe's example and in 1610 brought the work "up to the time of King James" and included a retelling of the French massacre. The 1632 edition added a topical outline and chronology, along with a "continuation of the foreign martyrs; additions of like persecutions in these later times" which included the Spanish invasion (1588), and the Gunpowder Plot (1605). The editor for the 1641 edition brought it to "the time of Charles, now King",and added a new copperplate portrait of John Foxe to accompany Simeon Foxe's "Life" of his father. The most "sumptuous" edition of 1684 anticipated James with gilt-edged, heavy bond paper and copperplate etchings that replaced worn-out woodcut illustrations.

As edition followed edition, Actes and Monuments or 'Foxe' began to refer to an iconic series of texts; unless constrained by a narrow band of time, Acts and Monuments has always referred to more than a single edition. The popular influence of the text declined, and by the nineteenth century it had narrowed to include mainly scholars and evangelicals. It was still sufficiently popular among them to warrant (at least) fifty-five printings of various abridgements in only a century, and to generate scholarly editions and commentary. Debate about Foxe's veracity and the text's contribution to anti-Catholic propaganda continued. Actes and Monuments survived whole primarily within academic circles, with remnants only of the original text appearing in abridgements, generically called The Book of Martyrs, or plain Foxe.

| Edition | Date | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Strasbourg Latin Edition | 1554 | persecution of Lollards |

| Basel Latin Edition | 1559 | "no more than a fragment" on Marian martyrs |

| 1st English Edition printed by John Day | March 1563 | "gigantic folio volume" ~1800 pages |

| 2nd Edition, with John Field | 1570 | response to Catholic critics; "two gigantic folio volumes, with 2300 very large pages" |

| 3rd Edition | 1576 | reprint, inferior paper, small type |

| 4th Edition | 1583 | last in Foxe's lifetime, "2 volumes of about 2000 folio pages in double columns" |

| Timothy Bright's Abridged Edition | 1589 | dedicated to Sir Francis Walsingham |

| Clement Cotton's Abridged Edition | 1613 | titled Mirror of Martyrs |

| Rev. Thomas Mason of Odiham's Abridged Edition | 1615 | titled Christ's Victorie over Sathans Tyrannie |

| Edition of the original | 1641 | Contains memoir of Foxe, now attributed to his son Simeon Fox. |

| Edward Leigh's Abridged Edition | 1651 | titled Memorable Collections |

| Jacob Bauthumley | 1676 | Brief Historical Relation of the Most Material Passages and Persecutions of the Church of Christ |

| Paul Wright | 1784 | The New and Complete Book of Martyrs, an update to cover the 18th century |

| Edition by Stephen Reed Cattley with Life and Vindication of John Foxe by George Townsend, in eight volumes | 1837–41 | Much criticised by Samuel Roffey Maitland on scholarly grounds. |

| Michael Hobart Seymour | 1838 | The Acts and Monuments of the Church; containing the history and sufferings of the martyrs; popular and reprinted Victorian edition. |

Latin versions

Foxe began his work in 1552, during the reign of Edward VI. Over the next thirty years, it developed from small beginnings (in Latin) to a substantial compilation, in English, filling two large folio volumes. In 1554, in exile, Foxe published in Latin at Strasbourg a foreshadowing of his major work, emphasising the persecution of the English Lollards during the fifteenth century; and he began to collect materials to continue his story to his own day. Foxe published the version in Latin at Basel in August 1559, lacking sources, with the segment dealing with the Marian martyrs as "no more than a fragment." Of course, it was difficult to write contemporary English history while living (as he later said) "in the far parts of Germany, where few friends, no conference, [and] small information could be had." He made a reputation through his Latin works. Both these versions were intended as the first volume of a two-volume work, the second volume to have a broader, European scope. Foxe did not publish these works; but a second volume to the Basel version was written by Henry Pantaleon (1563).

First edition

In March 1563, Foxe published the first English edition of The Actes and Monuments from the press of John Day. Day's epitaph reads: "He set a Foxe to write how martyrs run/By death to life. Foxe ventured pains and health/To give them light: Daye spent in print his wealth,/And God with gain restored his wealth again,/ And gave to him as he gave to the poor." It was a "gigantic folio volume" of about 1800 pages, about three times the length of the 1559 Latin book. As is typical for the period, the full title was a paragraph long and is abbreviated by scholars as Acts and Monuments. Publication of the book made Foxe famous; the book sold for more than ten shillings, three weeks' pay for a skilled craftsman, but with no royalty to the author.

Second edition

The second edition appeared in 1570, much expanded. New material was available, including personal testimonies, and publications such as the 1564 edition of Jean Crespin's Geneva martyrology. John Field assisted with research for this edition.

Acts and Monuments was immediately attacked by Catholics, including Thomas Harding, Thomas Stapleton, and Nicholas Harpsfield. In the next generation, Robert Parsons, an English Jesuit, also struck at Foxe in A Treatise of Three Conversions of England (1603–04). Harding, in the spirit of the age, called Acts and Monuments ' "that huge dunghill of your stinking martyrs," full of a thousand lies'. In the second edition, where the charges of his critics had been reasonably accurate, Foxe removed the offending passages. Where he could rebut the charges, "he mounted a vigorous counter-attack, seeking to crush his opponent under piles of documents." Even with deletions, the second edition was nearly double the size of the first, "two gigantic folio volumes, with 2300 very large pages" of double-columned text.

The edition was well received by the English church, and the upper house of the convocation of Canterbury meeting in 1571, ordered that a copy of the Bishop's Bible and "that full history entitled Monuments of Martyrs" be installed in every cathedral church and that church officials place copies in their houses for the use of servants and visitors. The decision repaid the financial risks taken by Day.

Third and fourth editions

Foxe published a third edition in 1576, but it was virtually a reprint of the second, although printed on inferior paper and in smaller type. The fourth edition, published in 1583, the last in Foxe's lifetime, had larger type and better paper and consisted of "two volumes of about two thousand folio pages in double columns." Nearly four times the length of the Bible, the fourth edition was "the most physically imposing, complicated, and technically demanding English book of its era. It seems safe to say that it is the largest and most complicated book to appear during the first two or three centuries of English printing history." At this point Foxe began to compose his interpretation of the Apocalypse; he wrote more in Eicasmi (1587), left unfinished at his death.

The 1583 title page included the poignant request that the author "desireth thee, good reader, to help him with thy prayer."

The Abridgements

The first abridgment appeared in 1589. Offered only two years after Foxe's death, it honoured his life and was a timely commemorative for the English victory against the Spanish Armada (1588). Issued with a dedication to Sir Francis Walsingham, Timothy Bright's tight summary of Acts and Monuments headed a succession of hundreds of editions of texts based on Foxe's work, whose editors were more selective in their reading. Based with greater or lesser degrees of exactitude on the original Acts and Monuments, yet influenced always by it, editors continued to tell its tale in both popular and academic venues (although a different tale was told to each gathering).

"The Book{s} of Martyrs"

The majority of the editors knew Foxe's text as a martyrology. Taking their material primarily from only the last two books of Acts and Monuments (that is, volume II of the 1570 edition), generated texts that genuinely were "Book(s) of Martyrs". Famous scenes from Acts and Monuments, in illustrated text, were revived for each new generation. The earliest printed book bearing the title, "Book of Martyrs", however, appears to be John Taylor's edition in 1631. While occurring again periodically, that title was not much in use before the mid-seventeen hundreds, and not regularized as the title of choice before 1850. The title, Foxe's Book of Martyrs (where the author's name reads as if part of the title) appears first in John Kennedy's 1840 edition, but this may be just a printing error.

Characterized by some scholars as "Foxe's bastards", these Foxe-derived texts have recently received increasing attention and recognition as the actual medium through which Foxe and his ideas influenced popular consciousness. Nineteenth-century professionalizing scholars, who wanted to keep separate their (academically significant) Acts and Monuments, clear from the abridgements' "vulgar corruption", dismissed these later editions as expressing "narrowly evangelical Protestant piety" and as nationalistic tools produced only "to club Catholics". Their judgment says more about their own prejudices that it does about any of these texts, as we know very little about any of these editions. Characterized most recently as 'Foxe', with ironic quotation marks signaling a suspect term, and also as "Foxe-in-action", these Foxe-derived texts have much yet to teach researchers about the nature of their subject.

Foxe as historian

The author's credibility was challenged as soon as the book first appeared. Detractors accused Foxe of dealing falsely with the evidence, of misusing documents, and of telling partial truths. In every case that he could clarify, Foxe corrected errors in the second edition and third and fourth, final version (for him). In the early nineteenth century the charges were taken up again by a number of authors, most importantly Samuel Roffey Maitland. Subsequently Foxe was considered a poor historian, in mainstream reference works. The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica accused Foxe of "wilful falsification of evidence"; two years later in the Catholic Encyclopedia, Francis Fortescue Urquhart wrote of the value of the documentary content and eyewitness reports, but claimed that Foxe "sometimes dishonestly mutilates his documents and is quite untrustworthy in his treatment of evidence".

Documented grounds

Foxe based his accounts of martyrs before the early modern period on previous writers, including Eusebius, Bede, Matthew Paris, and many others. He compiled an English martyrology from the period of the Lollards through the persecution of Mary I. Here Foxe had primary sources to draw on: episcopal registers, reports of trials, and the testimony of eyewitnesses. In the work of collection Foxe had Henry Bull as collaborator. The account of the Marian years is based on Robert Crowley's 1559 extension of a 1549 chronicle history by Thomas Cooper, itself an extension of a work begun by Thomas Lanuet. Cooper (who became a Church of England Bishop) strongly objected to Crowley's version of his history and soon issued two new "correct" editions. John Bale set Foxe onto martyrological writings and contributed to a substantial part of Foxe's ideas as well as printed material.

Objectivity and advocacy

Foxe's book is in no sense an impartial account of the period. He did not hold to later centuries' notions of neutrality or objectivity, but made unambiguous side glosses on his text, such as "Mark the apish pageants of these popelings" and "This answer smelleth of forging and crafty packing." David Loades has suggested that Foxe's history of the political situation, at least, is 'remarkably objective'. He makes no attempt to make martyrs out of Wyatt and his followers, or anyone else who was executed for treason, except George Eagles, whom he describes as falsely accused."

Sidney Lee writing in the Dictionary of National Biography called Foxe "a passionate advocate, ready to accept any primâ facie evidence". Lee also listed some specific errors and pieces of plagiarism. In developing the same metaphor, Thomas S. Freeman argues that Foxe "may be most profitably seen in the same light as a barrister pleading a case for a client he knows to be innocent and whom he is determined to save. Like the hypothetical barrister, Foxe had to deal with the evidence of what actually happened, evidence that he was rarely in a position to forge. But he would not present facts damaging to his client, and he had the skills that enabled him to arrange the evidence so as to make it conform to what he wanted it to say. Like the barrister, Foxe presents crucial evidence and tells one side of a story which must be heard. But he should never be read uncritically, and his partisan objectives should always be kept in mind."

By the end of the 17th century, however, the work tended to be abbreviated to include only "the most sensational episodes of torture and death" thus giving to Foxe's work "a lurid quality which was certainly far from the author's intention." Because Foxe was used to attack Catholicism and a rising tide of high-church Anglicanism, the book's credibility was effectively challenged in the early 19th century by a number of authors, most importantly Samuel Roffey Maitland. Dominic Trenow O.P. commented on Foxe's lost credibility across denominations, citing Maitland and Richard Frederick Littledale, as well as Robert Parsons and John Milner. In the words of this Victorian Catholic priest, after Maitland's critique and others of the time, Foxe's historical influence had been diminished so that "no one with any literary pretensions...ventured to quote Foxe as an authority."

The publication of J. F. Mozley's biography of Foxe in 1940 reflected a change in perspective that reevaluated Foxe's work and "initiated a rehabilitation of Foxe as a historian which has continued to this day." A new critical edition of the Actes and Monuments appeared in 1992.

"Since Mozley’s landmark study (1940)," Warren Wooden observed in 1983, "Foxe's reputation as a careful and accurate, albeit partisan, historian especially of the events of his own day, has been cleansed and restored with the result that modern historians no longer feel constrained to apologize automatically for evidence and examples drawn from the ‘’Acts and Monuments’’. Patrick Collinson's formal acknowledgement and recognition of "John Foxe as Historian," invites redetermining historians' current relationship with the text. John Foxe was the "greatest [English] historian of his age," Collinson concluded, "and the greatest revisionist ever".

Religious perspectives

For the English Church, Foxe's book remains a fundamental witness to the sufferings of faithful Christians at the hands of the anti-Protestant Roman Catholic authorities and to the miracle of their endurance unto death, sustained and comforted by the faith to which they bore living witness as martyrs. Foxe emphasizes the right of English people to hear or read the Holy Scripture in their own language and receive its message directly rather than as mediated through a priesthood. The valour of the martyrs in the face of persecution became a component of English identity. Roman Catholics consider Foxe a significant source of English anti-Catholicism, charging among other objections to the work, that the treatment of martyrdoms under Mary ignores the contemporary mingling of political and religious motives — for instance, ignoring the possibility that some victims may have intrigued to remove Mary from the throne.

Influence

Following a 1571 Convocation order, Foxe's Acts and Monuments was chained beside the Great Bible in cathedrals, select churches, and even several bishops' and guild halls; whereby God's truth reinforced local truth, and local truth, God's. Selected readings from the text were proclaimed from the pulpit as was (and as if it were) Scripture. It was read and cited by both ecclesiastical and common folk, disputed by prominent Catholics, and defended by prominent Anglicans. Acts and Monuments sailed with England’s gentleman pirates, encouraged the Saints in Oliver Cromwell’s army, and graced the halls at Oxford and Cambridge.

Acts and Monuments is credited as among the most influential of English texts. Gordon Rupp called it "an event". He counted it as a “normative document”, and as one of the Six Makers of English Religion. Nor was Foxe's influence limited to the direct effects of his text. At least two of Rupp's "makers" continued and elaborated Foxe's views. Christopher Hill, with others, has noted that John Bunyan cherished his Book of Martyrs among the few books that he kept with him while imprisoned. William Haller observed that John Milton's Of Reformation in England, and other tracts, took “not only the substance of the account…but also the point of view straight out of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments. Haller means by this, “the view of history advanced by propaganda in support of the national settlement in church and state under Elizabeth, kept going by the increasing reaction against the politics of her successors, and revived with great effect by the puritan opposition to Anglican prelacy in the Long Parliament.”

After Foxe's death, the Acts and Monuments continued to be published and appreciatively read. John Burrow refers to it as, after the Bible, "the greatest single influence on English Protestant thinking of the late Tudor and early Stuart period."

Position in English consciousness

The original Acts and Monuments was printed in 1563. This text, its dozens of textual alterations (Foxe's Book of Martyrs in many forms), and their scholarly interpretations, helped to frame English consciousness (national, religious and historical), for over four hundred years. Evoking images of the sixteenth-century martyred English, of Elizabeth enthroned, the Enemy overthrown, and danger averted, Foxe's text and its images served as a popular and academic code. It alerted English folk to the threat in harbouring citizens who bore allegiance to foreign powers, and it laid an anchor for their xenophobia. Acts and Monuments is academically linked with notions of English nationhood, liberty, tolerance, election, apocalypse, and Puritanism. The text helped to situate the English monarchy in a tradition of English Protestantism, particularly Whiggism; and it influenced the seventeenth-century radical tradition by providing materials for local martyrologies, ballads, and broadsheets.

In historiography

Warren Wooden presented John Foxe's key significance as a transitional figure in English historiography in 1983. "Foxe identified the key themes of the Reformation … along with the central props of Protestant belief." Wooden observed that Foxe also did much to determine the grounds of the controversy. By offering a full scale historical investigation, "Foxe helped to shape the controversy along historical and prophetic lines, rather than epistemological or linguistic ones.’ Patrick Collinson confirmed that Foxe was indeed a worthy scholar and that his text was historiographically reliable in 1985, and set in process the British Academy's funding for a new critical edition in 1984, completed by 2007.

Acts and Monuments acted as something of a Bible for English folk (commonly asserted) and also for academics (rarely acknowledged), influencing their histories, historical sensibility and consciousness to an unprecedented degree. University-trained researchers professionalized the original author's findings, his facts checked and challenged, being more often proved than not in seventeenth-eighteenth century inquiries, and their findings were verified through the next two centuries. Foxe's data and vision sensibly provided a foundation for informed academic conclusions. John Strype was among the early beneficiaries, and he praised John Foxe for preserving the documents on which his own ecclesiastical history depended.

Acts and Monuments substantially defined, among many other histories from John Strype onward, Arthur G. Dickens's influential The English Reformation (1964, 1989 revised), which has been characterized by a critic as “a sophisticated exposition of a story first told by John Foxe”. Why should that dependency be so worthy of comment? Dickens wrote a history that was informed by facts and—similarly to Milton—also the substance of his text, derived directly from Foxe's Acts and Monuments. Foxe's historical vision and the documentation to support it, was taught to young Arthur Dickens, along with his fellows, as a schoolboy.

Historiography, as the study of the writing of history, is in this case subsumed in history, as that which happened in the past and continues into the colloquial present. Discussing Foxe in the constructions of historical (national/religious) consciousness has always been also a discussion about the meaning and writing of history. Approaching this subject puts researchers into a kind of liminal zone between borders, where relations slip from one category to another – from writing history, to discussing history writing (historiography), to considering collective history in human consciousness (historical consciousness and collective memory).

The text in this case has always been multiple and complex. Several researchers have remarked on how malleable, how easily mutable Foxe's text was, and so inherently contradictory, characteristics that increased its potential influence. It is a difficult text to pin down, what Collinson called "a very unstable entity", indeed, "a moving target". ”We used to think that we were dealing with a book,” Collinson mused aloud at the third Foxe Congress (1999), “understood in the ordinary sense of that term, a book written by an author, subject to progressive revision but always the same book ... and [we thought] that what Foxe intended he brought about.”

Through the late nineties and into the twenty-first century, the Foxe Project has maintained funding for the new critical edition of Acts and Monuments and to help promote Foxeian studies, including five “John Foxe" Congresses and four publications of their collected papers, in addition to dozens of related articles and two specialized books or more produced independently.

Modern reception and anniversary

March 2013 will mark 450 years since Foxe's 1563 publication. Foxe's first edition capitalized on new technology (the printing press). Similarly, the new critical edition of Acts and Monuments benefits from, and is shaped by, new technologies. Digitalized for the internet generation, scholars can now search and cross-reference each of the first four editions, and benefit from several essays introducing the texts. The conceptual repertoire available for reading has so altered from that of John Foxe's era that it has been asked how it is possible to read it at all.

Patrick Collinson concluded at the third Foxe Congress (Ohio, 1999) that as a result of the " death of the author" and necessary accommodations to the "postmodern morass" (as he termed it then), The Acts and Monuments "is no longer a book [in any conventional sense]". If it is not a book, then what is it? We are not witnessing an end to reading. Rather, researchers are participating in the formulation of new understandings about how to read texts that aren't books, and learning to manage the emergence of subjects never before known.